No one likes traveling sick. In the perfect world no one would have to, but this isn’t a perfect world. We all have challenges; one of mine is being chronically ill.

I suffer from an extreme version of POTS (postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome). You can look up the specifics, but basically my heart and nervous system don’t communicate correctly so I will often pass out by sitting or standing. Along with the passing out, it basically makes you feel like garbage if you exert yourself in any way (extreme exhaustion, all over muscle aches, and a complete inability to focus). It’s not fun.

I had a dream to travel the world

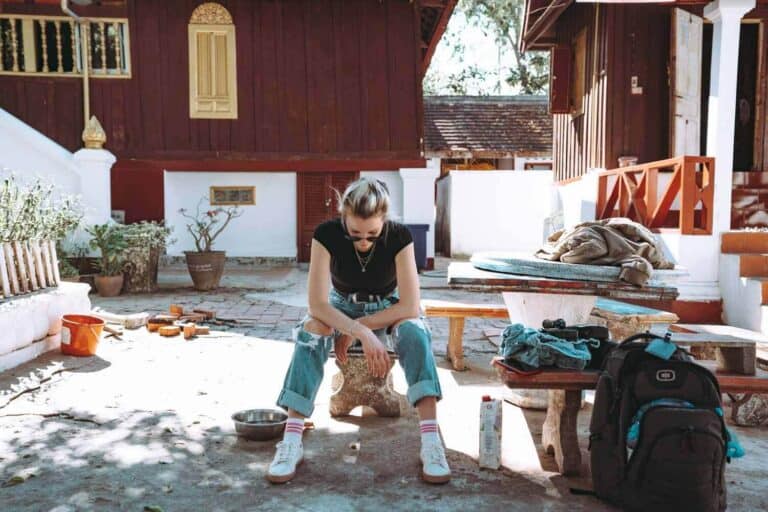

I always wanted to see the world. After years of being on bedrest I’d recovered to a point where I faced a tough decision.

Given that I still struggled with my condition, I could lay at home and be sick, or I could travel the world and be sick. Given that sickness was inevitable, I chose to travel.

Choosing to travel makes it sound easy, but long term sickness is no joke! It sucks the life out of you if you aren’t careful, and even if you are careful you are still probably getting the life sucked out of you. No victim of chronic illness is left unscathed.

So what’s my #1 travel secret?

My Travel Secret is to Think Negatively

To be able to travel while chronically ill you need to learn how to “think negatively”. I know that it sounds counterintuitive since there is so much evidence of the value of positive thinking, but keep reading.

Why?

You need to think negatively so you can be prepared for the worst case scenarios that will inevitably happen to a sick person.

Too many times I left the house thinking, hoping, and expecting to have a day where my symptoms didn’t flare up. This almost never happened, and ultimately left me in a much worse position.

A couple examples of times where I didn’t plan for the worst case scenario.

- I tried to go on a jog hoping that my health would hold up. It didn’t and I passed out in a ditch ½ mile from my house. I woke up in the ER to accusations of overdosing on drugs.

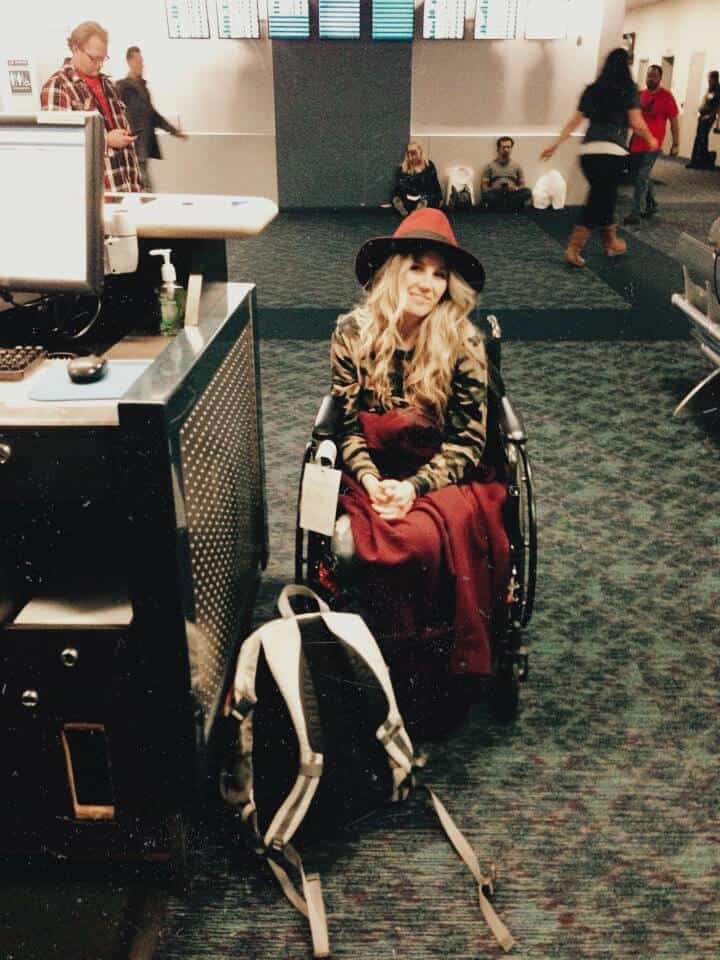

- I went on a trip to Alaska where I thought I could fly in on a redeye and immediately explore a glacier. I ultimately spent 3 days experiencing nothing but a hotel room bed. When I did finally try and make it home I passed out in the airport and missed three different flights.

- After a long flight I tried to walk through an airport instead of taking a wheelchair. I passed out and created a huge scene (my husband got accused of being a human trafficker for dragging me to our car). I knew I shouldn’t have attempted to walk to the car, but deep down I thought that if I told myself I could make it, then I would. That wasn’t true!

So where was my mistake? In both of those instances I didn’t plan for the worst case scenario, I only hoped for the best.

You don’t show up to the front lines not expecting to get shot at. A soldier at the front lines would need to show up with a sufficient amount of armor, and in those situations I had no armor.

So How do You Plan For the Worst Case Scenario? Negative Visualizations and Contingencies

As Ryan Holiday puts it in one of my favorite books The Obstacle is the Way, “We’re like runners who train on hills or at altitude so they can beat the runners who expected the course would be flat.”

If you are going to go on a trip you need to imagine what would happen if your worst symptoms came up at each step of the journey. What would happen if you are going through TSA when they arise, or in a taxi going to your hotel, or even getting on a roller coaster at Disney World? And then what would the contingency plan be if that negative event happened?

Now that you’ve imagined symptoms coming up at those awful times, what would you do about it?

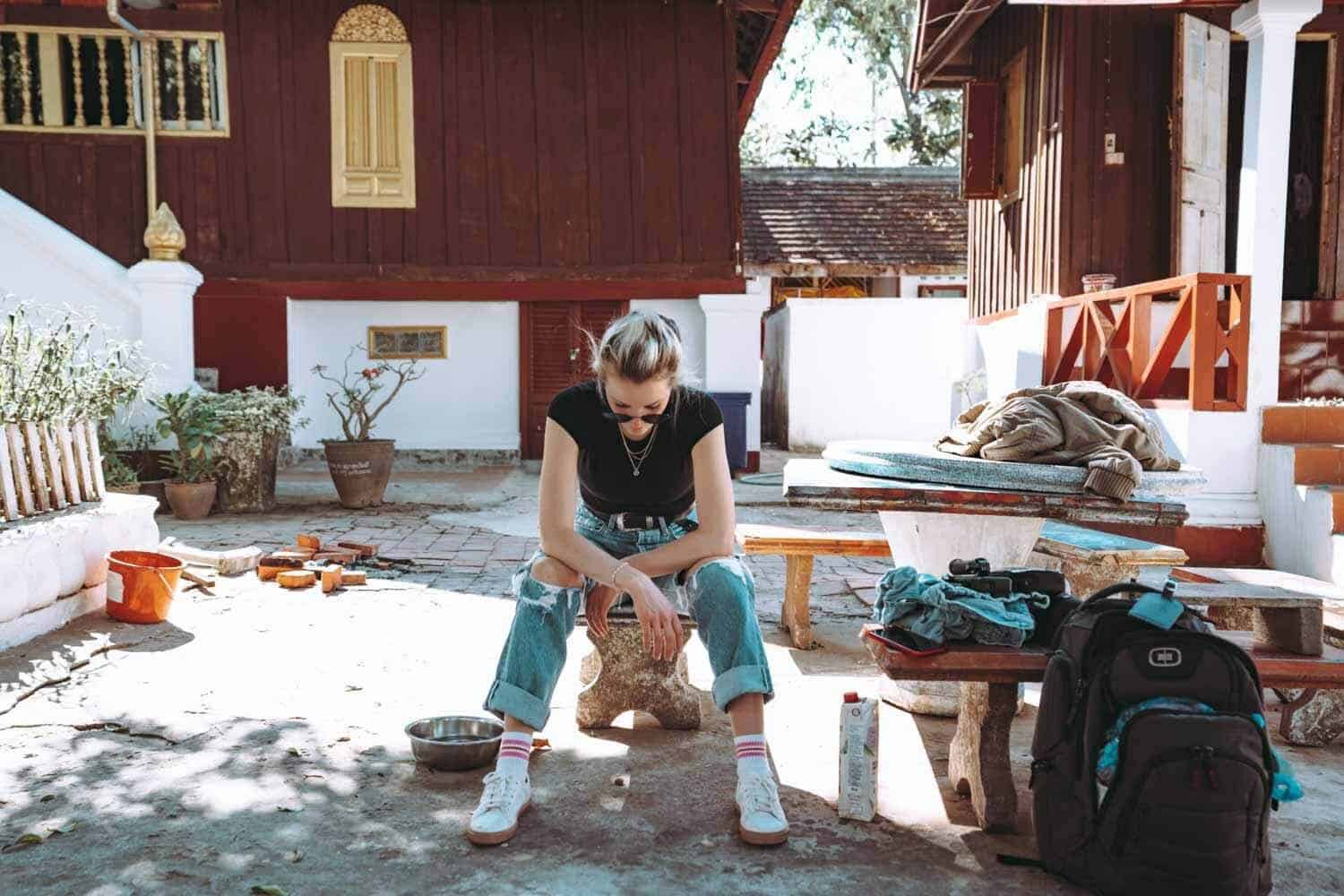

I love roller coasters and wanted to get back on one so bad. I knew that in an amusement park there were tons of things that could trigger an attack. Even though I felt great that morning, I planned ahead in case my symptoms arose. I reserved a wheelchair to take around the park, even though I felt fine in the morning. Sure enough, there came a point halfway through the day where I started to pass out and the wheelchair became an immediate necessity. My husband sat me in it and immediately wheeled me into air conditioning where I could lay down. Without preparing ahead of time, the result would have been much worse.

As Ryan Holiday puts it, “The world might call you a pessimist. Who cares? It’s far better to seem like a downer than to be blindsided or caught off guard.”

He goes on to say “It’s better to meditate on what could happen, to probe for weakness in our plans, so those inevitable failures can be correctly perceived, appropriately addressed, or simply endured.“

“Anticipation doesn’t magically make things easier, of course. But we are prepared for them to be as hard as they need to be, as hard as they actually are.“

The best way to try to prepare for a trip is by running negative visualizations through your head and planning contingencies for those visualizations.

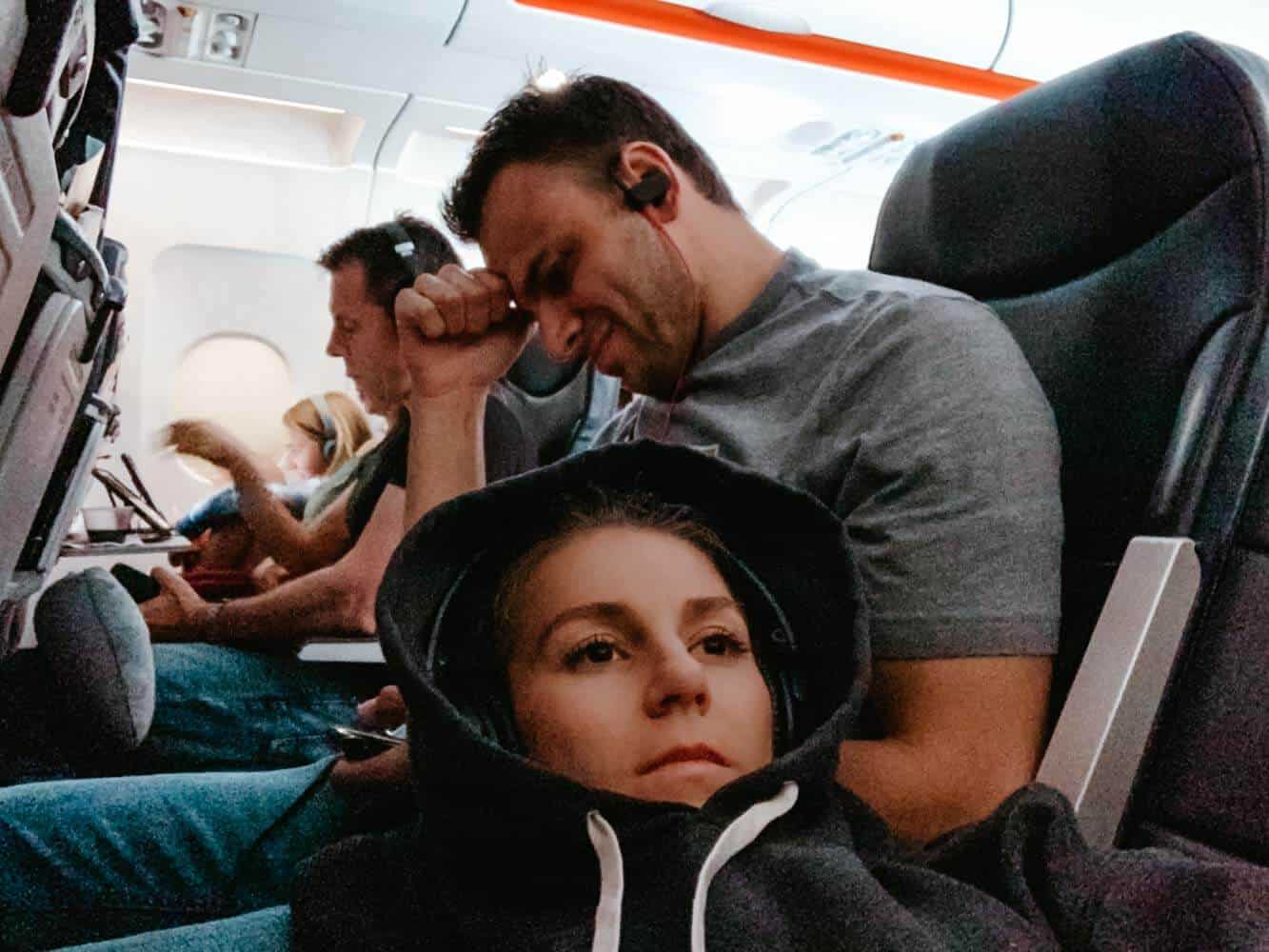

For me, my contingencies take many forms. Rather than flying alone, I will book a flight with a family member that is familiar with my condition in case something terrible happens. I will make sure I purchase a refundable ticket in case I’m not well enough to fly. I often make two different reservations to an attraction I really want to go to in case I am too sick on the first day.

On one trip to Hawaii I told the people seated around me on the plane that I have a condition that causes me to “pass out and shake” (convulsive syncope). I explained to them that this is “normal” for my condition and to not be alarmed if it happened. When it did happen they still got mildly freaked out, but not scream and make an emergency landing freaked out.

Hopefully you get the idea.

With travel, don’t set yourself up for failure by hoping your symptoms go away

With travel, don’t set yourself up for failure by hoping your symptoms will go away because you are on vacation. You know better. Even if the majority of a trip goes well, I know that at some point I’m going to have to deal with my illness, and I need to have a plan for that point. The absolute worst thing you can do is not be prepared when everything goes to hell.

By anticipating I prepare for the worst case scenario. In my experience the worst case scenario isn’t being super sick, it’s not properly preparing to be super sick.

Being sick doesn’t mean your life has to stop

Being sick doesn’t mean your life has to stop. You can become “good” at suffering, which to me means that I plan to do some things that I know will trigger my symptoms. I plan on encountering obstacles on my trips, but by having a plan for those episodes I’m able to suffer through them and find ways to still enjoy the trips.

Redefine success

A successful trip for the chronically ill needs to be substantially different than the average person. A successful trip for me is one where I get to explore 50% of the time rather than every day. Most people would call that a failure, but given that I’ve been on trips where I can’t even spend an hour a day outside of my hotel, 50% is an overwhelming success.

Make realistic plans for your trips and your life. What does successful mean to you?